Calculus &

Linear Algebra II

Chapter 34

34 Conservative vector fields

By the end of this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

- What is meant by a conservative vector field and a corresponding potential function?

- Given a potential function, how do you determine the corresponding conservative vector field?

- Given a conservative vector field, how do you determine a corresponding potential function?

34.1 Vector fields

In what follows, the notation is always \[ \r = x ~\i + y ~\j \;\; \text{ or } \;\;x ~\i + y ~\j + z~\k. \]

A vector field in the $x$-$y$ plane is a vector function of 2 variables

$\F\left(\r\right) $ $= \F(x,y) $ $= \big(F_1(x,y), F_2(x,y)\big)$

$=F_1(x,y)~\i + F_2(x,y)~\j.$

That is, associated to a point $(x, y)$ is the vector $\F (\r).$

34.1.1 Example: $\F (\r) = (-y, x) = -y~\i + x~\j.$

Similarly a vector field in 3-D is a vector function of 3 variables

| $\F(\r)$ | $=\F(x,y,z)$ |

| $=\big( F_1(x,y,z),F_2(x,y,z),F_3(x,y,z) \big)$ | |

| $=F_1(x,y,z)~\i+F_2(x,y,z)~\j+F_3(x,y,z)~\k$ |

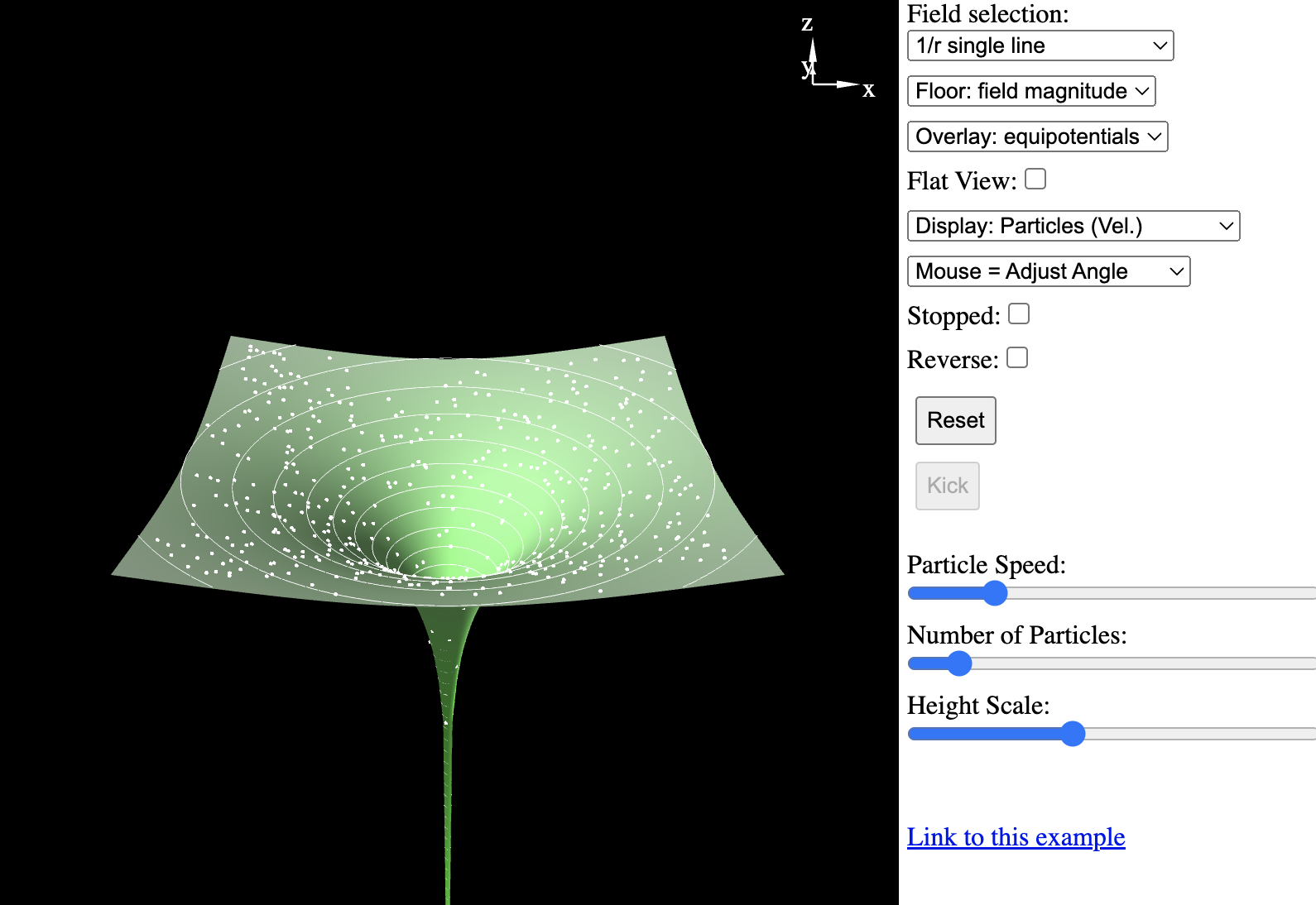

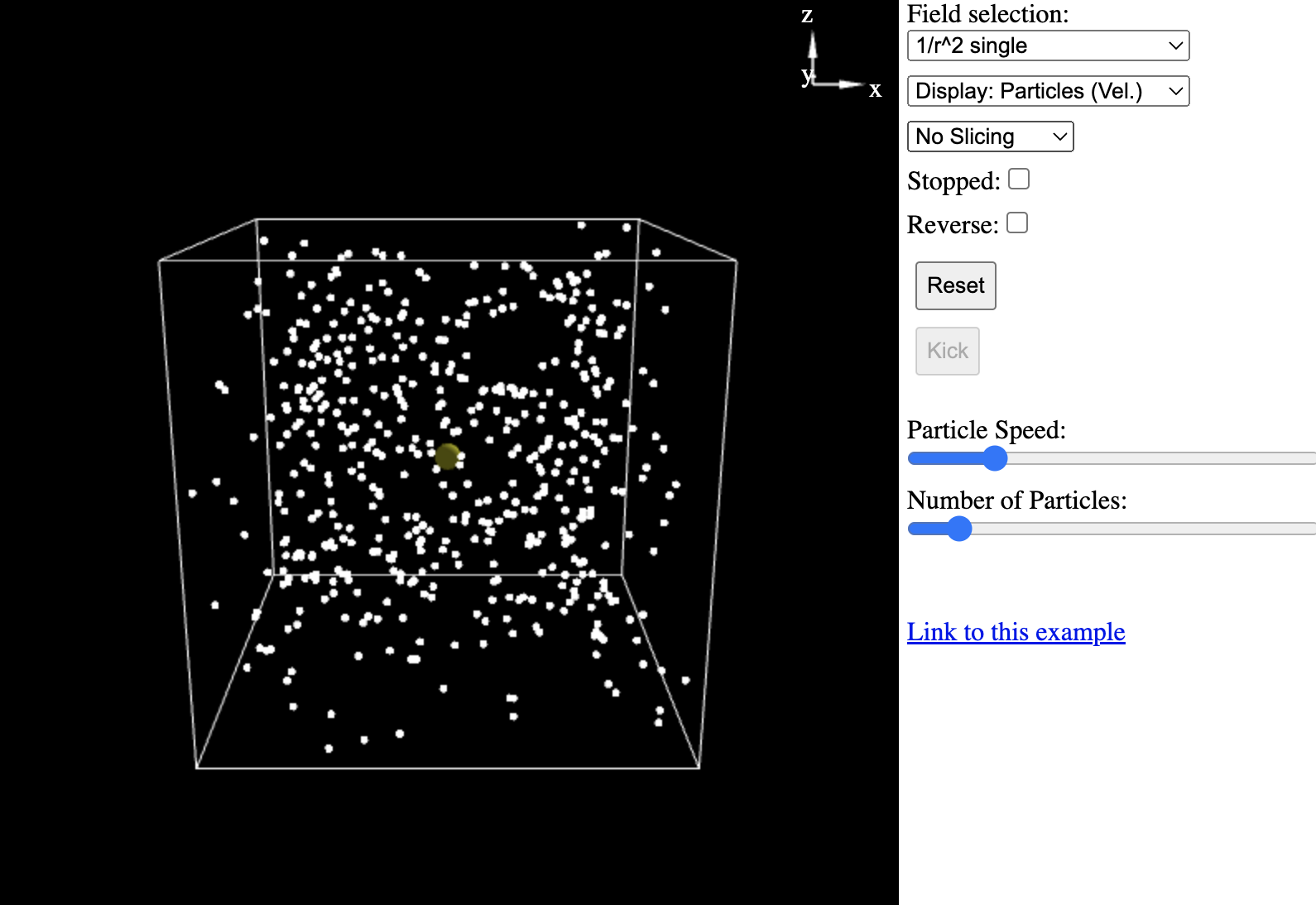

34.1.2 Example: Newtonian gravitational field

$\F(\r)$ $\displaystyle =\,-\frac{mMG}{||\r||^3}\r$ $ \displaystyle =\F(x,y,z)$

$\displaystyle \;\;=\frac{-mMG~x}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\i$ $\displaystyle +\,\frac{-mMG~y}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\j$

$\displaystyle +\,\frac{-mMG~z}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\k.$

34.1.2 Example: Newtonian gravitational field

34.2 Gradient of a scalar field, conservative vector fields

Recall for a differentiable scalar function $f(x,y)$ in two dimensions, we define

$\ds \text{grad }f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j.$

For a differentiable scalar function $f(x,y,z) $ in three dimensions, we define \[ \text{grad }f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j +\frac{\partial f}{\partial z}~\k . \]

Alternatively we define the differential operator $\displaystyle \nabla = ~\i \frac{\partial }{\partial x}+ ~\j \frac{\partial }{\partial y} + ~\k \frac{\partial }{\partial z},$

so $\;\text{grad } f = \nabla f.$

34.2.1 Example: find the gradient of $f(x, y, z) = x^2y^3z^4.$

| $\displaystyle \nabla f$ | $\displaystyle = ~\i \frac{\partial}{\partial x}\left(x^2y^3z^4\right)$ $\displaystyle + \,~\j \frac{\partial}{\partial y}\left(x^2y^3z^4\right) $ $\displaystyle+ \,~\k \frac{\partial}{\partial z}\left(x^2y^3z^4\right)$ |

| $\displaystyle = 2x~y^3z^4~\i $ $\displaystyle + \,3x^2y^2z^4~\j $ $\displaystyle + \,4x^2y^3z^3~\k $ |

Note $\nabla f$ is a vector. It's length and direction are independent of the choice of coordinates. $\nabla f$ (evaluated at a given point $P$) is in the direction of maximum increase of $f$ at $P$.

For example at $(1,1,1),$ we have that \[ \nabla f (1,1,1) = 2~\i + 3 ~\j + 4~\k. \]

Gradient of $f(x, y)$ visualisation

34.2.1 Example: find the gradient of $f(x, y, z) = x^2y^3z^4.$

You may see the scalar function $f$ referred to as a scalar field. If a vector field $\v$ and a scalar field $f$ are related by $\v = \nabla f,$ we call $f$ a potential function and $\v$ a conservative vector field.

34.2.2 Verify that the Newtonian gravitational field is conservative with potential function $f(x,y,z)= \frac{mMG}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}.$

First, note that $\displaystyle f(x,y,z) = mMG\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{-1/2}$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} $ $\displaystyle =mMG$ $\displaystyle \left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{-3/2} $ $\displaystyle \left(2x\right)$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} $ $\displaystyle =mMG\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{-3/2}\left(2y\right)$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial z} $ $\displaystyle =mMG\left(-\frac{1}{2}\right) \left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{-3/2}\left(2z\right)$

34.2.2 Verify that the Newtonian gravitational field is conservative with potential function $f(x,y,z)= \frac{mMG}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}.$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial x} = - \frac{mMG~x}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial y} = - \frac{mMG~y}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}$

$\displaystyle \frac{\partial f}{\partial z} = - \frac{mMG~z}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}} $

34.2.2 Verify that the Newtonian gravitational field is conservative with potential function $f(x,y,z)= \frac{mMG}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}.$

| $ \displaystyle \nabla f$ | $\displaystyle = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j + \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}~\k$ |

| $\displaystyle = \frac{-mMG~x}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\i $ $\displaystyle +\, \frac{-mMG~y}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\j $ | |

| $\ds \qquad\qquad +\,\frac{-mMG~z}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}}~\k$ | |

| $\displaystyle= -\frac{mMG}{\left(x^2+y^2+z^2\right)^{3/2}} \big(x~\i + y ~\j + z ~\k\big)$ |

34.2.2 Verify that the Newtonian gravitational field is conservative with potential function $f(x,y,z)= \frac{mMG}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}.$

| $\displaystyle \nabla f$ | $\displaystyle = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j + \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}~\k$ |

| $\displaystyle= -\frac{mMG}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}} \big(x~\i + y ~\j + z ~\k\big)$ | |

| $\displaystyle = -\frac{mMG}{(x^2+y^2+z^2)^{3/2}}\r$ $\displaystyle = -\frac{mMG}{||\r||^3}\r$ $\displaystyle = \F(\r)$. |

34.2.2 Verify that the Newtonian gravitational field is conservative with potential function $f(x,y,z)= \frac{mMG}{\sqrt{x^2+y^2+z^2}}.$

Therefore, the graviational vector field \[ \F(\r) = -\frac{mMG}{||\r||^3}\r \] is a conservative vector field.

Given a conservative vector field, how can we determine a corresponding potential function? The next example outlines this procedure.

34.2.3 The vector field $\F (x, y) = \left(3 + 2xy\right)~\i +

\left(x^2 - 3y^2\right)~\j$

is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

Conservative means that there exists a function $f$ such that

$\F = \nabla f$ $\displaystyle =\frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j$.

Then we have that \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= &3 + 2xy\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = &x^2-3y^2 \end{array} \right. \]

34.2.3 The vector field $\F (x, y) = \left(3 + 2xy\right)~\i +

\left(x^2 - 3y^2\right)~\j$

is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= &3 + 2xy\quad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = &x^2-3y^2\;\; (2) \end{array} \right. $ |

Choose equation (1) and integrate both sides with respect of $x$ to obtain \[ f= 3x+x^2y+g(y) \] Now differentiate this function with respect of $y$: \[ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} = 0 + x^2 +\dfrac{\partial g(y)}{\partial y} \] |

|---|

34.2.3 The vector field $\F (x, y) = \left(3 + 2xy\right)~\i +

\left(x^2 - 3y^2\right)~\j$

is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= &3 + 2xy\quad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = &x^2-3y^2\;\; (2) \end{array} \right. $ |

Compare $\dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} = x^2 +\dfrac{\partial g(y)}{\partial y}$ with (2), so \[ x^2-3y^2 = x^2+ \dfrac{\partial g(y)}{\partial y} \] \[ \dfrac{\partial g(y)}{\partial y} = -3y^2 \] \[ g(y) = -y^3 + C. \] |

|---|

34.2.3 The vector field $\F (x, y) = \left(3 + 2xy\right)~\i +

\left(x^2 - 3y^2\right)~\j$

is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

Finally, we substitute into $f = 3x+x^2y+g(y)$ to obtain \[ f(x,y) = 3x+x^2y-y^3+C. \]

Can we still determine a potential function when the conservative vector field is in three dimensions?

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

Conservative means that there exists a function $f$ such that \[ \F = \nabla f = \frac{\partial f}{\partial x}~\i + \frac{\partial f}{\partial y}~\j+ \frac{\partial f}{\partial z}~\k \]

Then we have that \[ \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= & y^2\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = & 2xy+e^{3z}\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}& = & 3y e^{3z} \end{array} \right. \]

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= & y^2\;\;\;\,\,\qquad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = & 2xy+e^{3z} \;\;\,(2)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}& = & 3y e^{3z} \;\qquad(3) \end{array} \right. $ |

Choose equation (1) and integrate both sides with respect of $x$ to obtain \[ f= xy^2+g(y,z) \] Now differentiate this function with respect of $y$: \[ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y} =2xy +\dfrac{\partial g(y,z)}{\partial y} \] |

|---|

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= & y^2\;\;\;\,\,\qquad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = & 2xy+e^{3z} \;\;\,(2)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}& = & 3y e^{3z} \;\qquad(3) \end{array} \right. $ |

Compare $2xy +\dfrac{\partial g(y,z)}{\partial y}$ with (2), so \[ 2xy+e^{3z} = 2xy +\dfrac{\partial g(y,z)}{\partial y} \] \[ \dfrac{\partial g(y,z)}{\partial y} = e^{3z} \] \[ g(y,z) = ye^{3z} + h(z). \] |

|---|

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= & y^2\;\;\;\,\,\qquad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = & 2xy+e^{3z} \;\;\,(2)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}& = & 3y e^{3z} \;\qquad(3) \end{array} \right. $ |

Substitute into $f = xy^2+g(y,z)$ to obtain \[ f(x,y) =xy^2+ye^{3z}+h(z). \] Differentiate $f$ with respect to $z$ \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial z} = 0 + 3ye^{3z} + \frac{\partial h(z)}{\partial z}. \] Compare with (3) to obtain $\displaystyle 3ye^{3z} = 3ye^{3z}+ \frac{\partial h(z)}{\partial z} $ |

|---|

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

|

$ \displaystyle \left\{ \begin{array}{rl} \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial x} &= & y^2\;\;\;\,\,\qquad (1)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial y}& = & 2xy+e^{3z} \;\;\,(2)\\ \dfrac{\partial f}{\partial z}& = & 3y e^{3z} \;\qquad(3) \end{array} \right. $ |

Substitute into $f = xy^2+g(y,z)$ to obtain \[ f(x,y) =xy^2+ye^{3z}+h(z). \] Differentiate $f$ with respect to $z$ \[ \frac{\partial f}{\partial z} = 0 + 3ye^{3z} + \frac{\partial h(z)}{\partial z}. \] Compare with (3) to obtain $\displaystyle \frac{\partial h(z)}{\partial z} = 0$ $\;\;\Rightarrow \;\;h(z) = \text{constant}$. |

|---|

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

Therefore the function \[ f(x,y,z ) =xy^2+ye^{3z}+C \] is the scalar potential such that \[ \F = \nabla f. \]

34.2.4 The vector field $ \,\F(x,y,z) = y^2~\i + \left(2xy + e^{3z}\right)~\j + 3ye^{3z}~\k\,$ is conservative. Find a corresponding potential function.

Is there a way of determining whether or not a given vector field is conservative? To answer this question, we need to go back to the study of line integrals.